Eric Ward, a graduate student at MIT, has always wanted to work in the aerospace industry. “It’s a field full of people who are both very passionate about space and also excited about tackling very hard problems,” he says.

After earning a degree in mechanical engineering, Ward landed coveted internships at NASA and Lockheed Martin Aeronautics, expecting that he would spend his entire career at a big, established space company. But over the last decade, he’s watched a new generation of companies like Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin, and SpaceX enter the space game. “There’s a mythos in the space community surrounding Elon Musk,” Ward says, referring to the founder of SpaceX. “He’s been very successful in changing the way people think about space. He’s forced people to accept that fact that the private space sector is viable and important for the growth of the industry.”

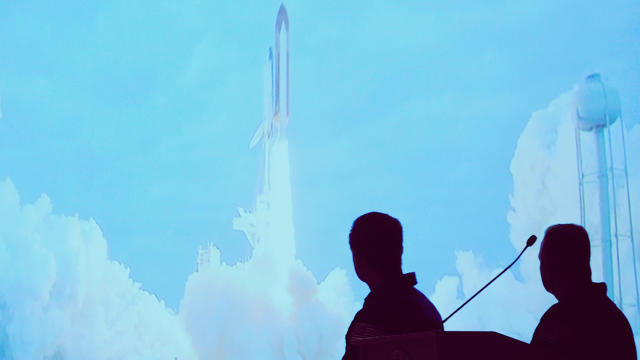

The success of these high-profile companies has inspired other entrepreneurs—or astropreneurs, as they sometimes refer to themselves—to take a stab at starting their own space businesses. NewSpace Global, a firm that tracks the private space industry, has seen explosive growth in the market. Over the last five years, it’s gone from tracking 125 space companies to over a thousand. “We expect to be at 10,000 in the next ten years,” Richard Rocket, NewSpace Global’s CEO, said during a presentation at MIT’s New Space Age conference. “There are more companies emerging that are capable of sending something to space. That’s exciting because it’s going to drive down launch costs and increase launch rates. They’ll help prove that these business models work.”

Ward wants to be part of this new breed of space startups. Over the last year, while working on a degree in systems design and management at MIT, he’s been tinkering with the design of a rocket that will send small satellites into orbit. With a cofounder, he’s currently working on a business plan to secure funding.

The Booming Business in Small Satellites

Ward’s startup, like many others that are springing up, is capitalizing on the boom in small satellites.

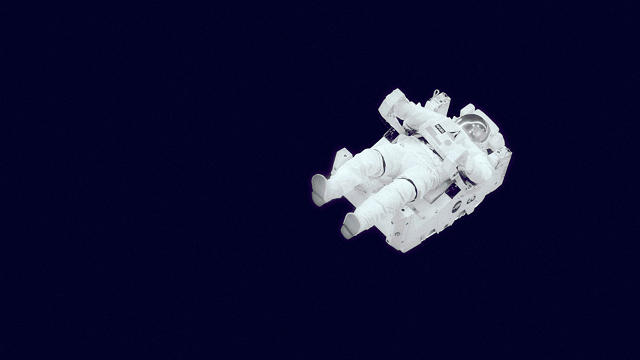

Small satellites first gained popularity over a decade ago, when universities like Cal Poly and Stanford started encouraging students to build CubeSats—mini satellites weighing less than three pounds—that would go into space to gather scientific information, observe Earth, and even launch amateur radio stations. Through a NASA educational program, CubeSats would be selected to piggyback on space missions. NASA currently has 50 more CubeSats awaiting launch.

But over the last few years, companies have been eager to develop small satellites of their own to gather data for their businesses or test out technology. The global satellite industry is now valued at over $200 billion and is rapidly growing. More satellites were launched into space in 2015 than ever before.

Startups are coming up with more and more uses for these satellites. Two years ago, Google acquired Skybox, which uses CubeSats to provide high-resolution photos and videos of the earth. Mark Zuckerberg’s plan to bring affordable Internet to the entire world will depend on satellite technology. Small satellites have been used to more precisely detect weather patterns, closely monitor crops, provide real-time images of Earth, and even identify how many cars are in a parking lot.

The market is now ready for rockets whose only purpose is to carry small satellites. NASA is currently developing its own rockets to do this, and it is investing in other companies that are working on technologies specifically designed to launch small satellites. L.A.-based Rocket Labs has already developed a vehicle called “Electron” that provides low-cost, high-frequency launches for small satellites. It has one big contract for 12 launches over 18 months as soon as its facility in New Zealand is complete. Another company, Firefly Space Systems, offers a similar vehicle, and has secured a $5.5 million deal with NASA to launch a constellation of CubeSats in 2018. Virgin Galactic and SpaceX are also working to provide this service.

Ward believes there is room in the market for many more companies like this, given the many small satellites that are currently looking to hitch a ride into space. Right now, companies need to wait two years to send a small satellite into orbit. “We will provide the transportation infrastructure to the rapidly growing small satellite market,” Ward tells Fast Company.

Space Angels

Over the last year, Ward and his cofounder have been designing the hardware to launch these small satellites. With their engineering background, they have the technical skills to develop a rocket, but in order to get a vehicle off the ground (literally), they will need a significant amount of capital investment. This is why they are at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, acquiring the skills they need to launch a business.

From Ward’s current projections, he believes several million dollars in funding should allow them to make progress, though it will take up to $50 million to be fully up and running. Fortunately, there are investors eager to pour funds into startups like Ward’s. For instance, there’s the New York-based Space Angels Network that invests in early stage space startups. The group receives hundreds of applications from startups every year, and invests in about 5% of them. “You’re looking at investment profiles closer to biotech,” Ward said. “Higher capital costs, longer duration investments, but the potential for these even bigger payouts.”

There are also space incubators that help astropreneurs go from an idea to a business plan. The Silicon Valley Space Center and Lightspeed Innovations are both aerospace accelerator programs that help promising entrepreneurs land angel funding. “We’re using the TechStars model,” Ellen Chang, Lightspeed’s founder, said at the MIT conference. “We’re focusing in on 10 companies, and our challenge is to get to the point where they are investable in four or five months.” Last year, for instance, Lightspeed helped to secure investment for Phase Four, a startup developing plasma-based technologies to propel satellites into space. It also helped Kubos, another early stage startup that is building open source software to support small satellite missions.

Because space travel is so complex, startups are rushing in to meet very specific, specialized needs. Astroscale, for example, is a Singapore-based startup developing a satellite that will remove orbital debris and decommissioned spacecraft from space. It hopes to have a demonstration mission in 2017 and to be fully operational 2018. Last month, it secured $35 million in funding from a group of venture capitalists investors from around the world.

Besides launching spacecraft and satellites, startups are also analyzing vast quantities of new data and sorting out communication systems so that information can pass from Earth to space and back again. On the backend, there needs to be extensive resources to coordinate and manage missions from the ground. These different companies are working together, creating a new ecosystem.

Google’s acquisition of Skybox Imaging in 2014 for $500 million, only four years after the company was created, sent a ripple through the investment community, signaling that space startups had the potential to make big, profitable exits in a short amount of time. “Skybox will not be an outlier,” Rocket said. “We will see an increase in the number of space unicorns with valuations of north of a billion dollars, though this might take several years.”

Space 3.0

Lisa Porter, who has held top positions at NASA, DARPA, and other intelligence wings of the government, says that we’re now in the third chapter of the space industry. “We call it Space 3.0,” she said. At first, governments invested heavily in space exploration; then companies with large budgets entered the industry. “There are new opportunities and new capabilities now,” she explained. “The distinction is that they are all driven by cost innovation. The mindset is first and foremost about getting the cost very low.”

Rocket Labs is a good example of this thinking at work. It has managed to create a vehicle that will drive down the cost of sending a rocket into space to $4.9 million per launch, 95% less than the average cost right now.

For someone like Ward, who is just getting his feet wet as an astropreneur, it still feels like there are gaps in the market, particularly if he focuses on creating a system for getting satellites into space that is cheaper than those of his competitors. While starting a space company is daunting, it does not seem impossible. “Launching a space startup is very much a doable thing,” says Sean Casey, the founder of the Silicon Valley Space Center. “There is still room for a lot of additional players.”

That’s not to say that it will be easy. In fact, Ward expects it to be the biggest challenge of his life. He’s been brainstorming names for his new company and recently, he settled on Odyne Space. “She’s the Greek goddess of pain,” he says.