For years, the conventional wisdom about Amazon’s Kindle e-reader was that the company, which likes to say that it wants to make money when customers use its products, would eventually make buying e-books irresistible by offering a Kindle e-reader for free. But Amazon has refused to play along. For the time being, the cheapest Kindle is $80, which is actually 10 bucks more than the least expensive model of a few years ago.

My hunch is that Amazon isn’t under much pressure to slash Kindle prices to nothing—or at least next to nothing—because most of us already own free Kindle e-readers, in the form of smartphones that can run the company’s Kindle app. That’s left the company free to pursue a strategy that I sure didn’t see coming: It’s been releasing ever-more refined, high-end Kindle e-readers, aimed at people who love the idea of a device that’s optimized for reading, and only reading.

This trend became clear in 2014, when Amazon released the $200 Kindle Voyage. With its sleek industrial design and ultra-readable E Ink display, it supplanted the Kindle Paperwhite as the the top-of-the-line Kindle.

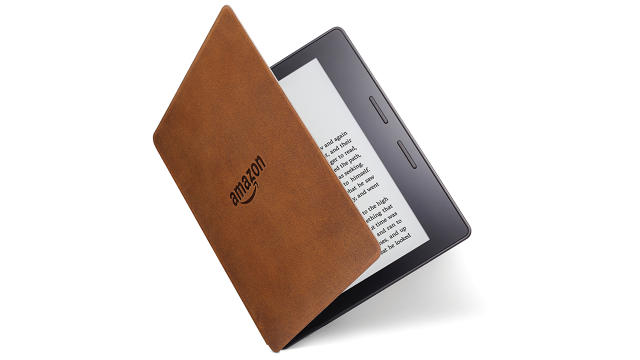

And now the company is introducing the Kindle Oasis, teased by Jeff Bezos last week and then leaked in more or less its entirety. The $290 model, which starts shipping on April 27, does to the Voyage what the Voyage did to the Paperwhite. But it accomplishes that with some new twists which, if it weren’t for the leak, would be wholly unexpected.

Thinner And Thicker

In designing the Oasis, Amazon made most of the device really thin via a unique design gambit: It shoved most of the electronics into an thicker, 8.5mm pod on the left-hand side of the device. (Or, if you choose, the right-hand side—the e-reader has an accelerometer, and will flip the display around if you rotate it by 180 degrees.) That let it shave the rest of the case down to 3.4mm, or less than half the thickness of the Voyage. The thick-thin design gives the Oasis a handle of sorts and evokes both a folded-back dead-tree paperback and the original 2007 Kindle, which sported a quirky angled case that disappeared in the second-generation model.

Amazon also greatly reduced the e-reader’s bezel—except on that edge with the rear hump, which provides room for page-turning buttons—leaving the case size far more pocketable than before. It’s so diminutive that you might be tempted to call it the Kindle Mini, if it weren’t for the fact that the display size remains 6″, the same as with nearly every other Kindle ever made. This time around, the monochrome E Ink display isn’t a radical upgrade from the excellent 300-dpi version in the Voyage, but Amazon did move the LED lighting from the bottom of the screen to the side, thereby allowing it to boost the brightness by squeezing in additional LEDs.

One of the Kindle’s signature features has always been its marathon battery life—up to six weeks in the case of the Voyage, assuming that you read on average for a half hour a day. I always assumed that such endurance was sacrosanct, but with the Kindle Oasis, Amazon has messed with its recipe in a new way. The device is so small and thin that it packs a rather dinky battery, which Amazon says provides up to two weeks of power, again based on an average of 30 minutes of reading a day. But every Oasis comes with a posh leather case with a much beefier built-in battery. The case snaps on magnetically—its battery sits next to the hump on the e-reader, and fills in the surrounding area—turning the whole package into an e-reader that can run for up to two months, a new Kindle record.

When the Oasis is in its case, it automatically draws power from the battery; if you plug it into power, the e-reader and case charge as if they were one. And the cases, which are available in three styles, are beautifully crafted. Basically, you can choose between having a really thin Kindle with reasonable battery life and a chunkier one with incredible battery life, and switch back and forth on the fly.

Judging from a bit of hands-on time I had with a Kindle Oasis during a briefing by Amazon executives, the device pushes the Kindle line a bit closer to the original vision that Jeff Bezos articulated back in 2007, which was that a Kindle should disappear in your hands. It looks wonderfully polished. But it’s polished in an idiosyncratic, Amazonian way. I can’t imagine that cramming all the electronics in a gadget into a lump on one side will start a trend among other gadget makers, and many Kindle aficionados, I suspect, will be perfectly happy with the battery life of a lesser Kindle.

At $280, the Oasis is the priciest e-reader that Amazon has offered in many years, and it may cater to a niche rather than being the romantic ideal of every Kindle still to come. Anyone who doesn’t want to pay that sort of money for a Kindle still has lots of options. All the current models will remain on the market: the $200 Kindle Voyage, the $120 Paperwhite, and the $80 plain old Kindle.

In an era of smartphones and tablets, you might assume that a monochromatic computer devoted to reading would be an anachronism, doomed to suffer through a long decline until it finally goes away. But Amazon, which is famous for not providing actual sales figures for its products, says that Kindle sales continue to grow. The arrival of the Oasis is confirmation that the device has avoided the fate of a frozen-in-time gizmo such as iPod: It’s not just still on the market, but evolving in ways that go beyond superficial tweaks and cost reductions. For now, at least, there’s life in the old e-reader yet.